Fright Night at 25: Writer/Director Tom Holland

With Fright Night celebrating its 25th anniversary, while plans are underway for a remake, Earth's Mightiest salutes the film beginning with this interview with writer/director Tom Holland.

The discussion covers three of Holland's genre films: Psycho II, for which he supplied the script to the Richard Franklin-directed effort; Fright Night and the original Child's Play.

Interview conducted by and copyright Edward Gross

This interview with director Tom Holland was conducted while he was in the midst of production on the original CHILD’S PLAY, which has spawned three sequels with a fourth on the way. Since that time, Holland’s directorial credits include the TV mini-series STEPHEN KING’S THE LANGOLIERS, and the feature film adaptation of King’s THINNER.

Try as he might, writer/director Tom Holland seems unable to avoid the horror genre, despite warnings from his peers that it would be, if you'll pardon the expression, death to be trapped there.

After making his directorial debut on the highly successful FRIGHT NIGHT, Holland searched for something that would be completely different, and found it in Whoopi Goldberg's FATAL BEAUTY. Unfortunately, the film was so poorly received both critically and commercially, that it is not even listed among his credits. Moving back into more familiar territory, he next gave audiences CHILD'S PLAY, which was a tremendous hit, re-establishing Holland and making Chucky a household name.

Beginning as an actor before seguing to the roles of screenwriter and director, Tom Holland has quite literally climbed the motion picture ladder of success, fulfilling a dream he's had since childhood.

"I've always been interested in film," Holland explains reverently. "When I was four or five, I was glued to the television, and I went to see every movie that I could. I don't think that I really cared about anything else."

His entry level in the business, as stated before, was as an actor, appearing in over 250 commercials, three soap operas (LOVE OF LIFE, FLAME IN THE WIND and A TIME FOR US) and films such as THE MODEL SHOP and A WALK IN THE SPRING RAIN. Feeling creatively stifled, he turned his talents to writing.

"When I got in the business," says Holland, "I didn't know it would take so long to learn to write. I've worked my way through writing into directing. I was so naive. I came out in the early '70s, and that was at the time when all these original screenplays were going for $250,000. Then those screenwriters would turn around and direct. There were a lot of guys around who seemed to be doing it, and I thought I'd sit down, whip off a screenplay for a quarter of a million dollars, then write another one and direct it. I had no idea how hard writing was. So, ten years later, after I had, to some degree, mastered the craft of storytelling in a screenplay, I finally felt I could go on and direct. It's been a very slow, but sane forward progression."

This progression resulted in the screenplays for THE BEAST WITHIN, THE CLASS OF 1984 and SCREAM FOR HELP, a Hitchcockian tale in which a young girl suspects that her stepfather plans on murdering her mother, but can't prove it. The latter led to what may be considered one of Holland's most prestigious scripts, PSYCHO II.

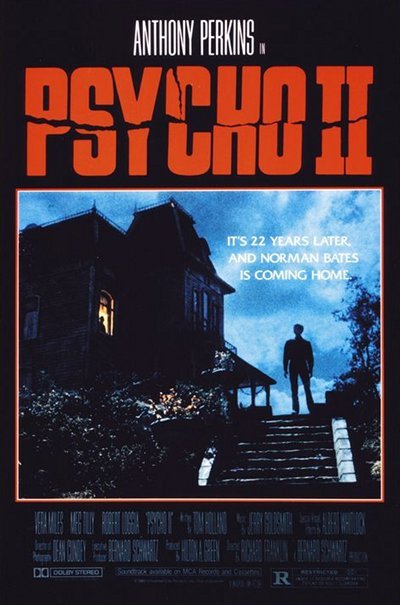

"From what I understand," recalls Holland, "Robert Bloch had done a novel called PSYCHO II, then came to Universal and suggested that they make it into a film. They didn't like his book, but they thought the idea of a sequel was a great one. Richard Franklin was chosen as director, and while he was reading material looking for a writer, he found SCREAM FOR HELP. On that basis, he hired me. Then the question was, what the hell was the story going to be."

The answer was soon evident. PSYCHO II, taking place 22 years after the original, begins with Norman Bates being set free from the mental institution, and trying to get his life on track again. Unfortunately, Lila Loomis (Vera Miles), sister of the slain Marion Crane (see the original), wants revenge and sets about driving Norman crazy again. Needless to say, it's only a short matter of time before she's successful, and Mother makes a return appearance.

"I was trying desperately to be respectful," Holland says. "I didn't want to do a slasher film, but at the same time, as you can tell from some parts of the film, there was a feeling from the studio that there should be enough shock moments to satisfy that 'slice and dice' crowd out there. Given today's market, I couldn't really disagree with them. It was also, if you think about it historically, the first PSYCHO that opened up the whole genre.

"I don't think anybody picked up a knife and graphically did somebody in until Hitchcock got Janet Leight in the shower," he elaborates. "I think that sort of set everybody's mind working. They took it a lot farther, God knows. The serial murders, the nonstoryline murders, may have started with HALLOWEEN or FRIDAY THE 13TH, but I don't think the graphic killings would have been possible without Hitchcock opening it up to a whole new emotional level in PSYCHO."

He collaborated with Richard Franklin again on CLOAK AND DAGGER, a kids and espionage film, and followed with the opportunity to write and--finally--direct FRIGHT NIGHT.

"There's an old saying that writers direct in self defense," Holland laughs. "FRIGHT NIGHT marks the first time I can't say that the director didn't do it the way I intended it to be done. Often times a film turns out very well, but it's not quite what I would have liked it to be. They may have been no worse, they may have been no better, but there were choices I would not have made. Whenever you have a mediating factor of someone else interpreting your material, it always changes and not always for the best."

One must wonder what the primary difference is between writing a film, and writing and directing one. On the one hand, a person who "just" writes has to step away from it, but on the other he or she is seeing it through completion.

"The quick answer is the hours," he responds, "but they are two different functions. As you know, writing is almost asocial, which is one of the wonderful things about it. Directing is an extremely social activity, because you're dealing with a large number of people. God, I'm one of the few people who could answer that honestly...it's really a valid question. I think a lot of writers are mainly verbal; they hear dialogue. I think I tell the story in more of a visual way. In every one of my scripts, I've had at least three visual set pieces which move the story ahead visually with a minimal amount of dialogue. Often the director receives credit for that, even though it was written in the script. Because I think that way, perhaps I was a little bit more prepared to direct. Maybe more than a lot of other people.

"When you're writing, you can tell a story verbally, with words. When you're directing, you've got to let go of the words and figure out how to do it visually, where every image has to move the story forward. When you're writing a screenplay, you have to try to structure it where every scene moves it forward, but it's a very different conceptual way of thinking. It's very difficult to describe.

"On FRIGHT NIGHT, I finished writing the script, did the various revisions, took off my writer's hat, put on my director's hat and sat down. I did my own storyboards, telling the story in a shot-by-shot breakdown, so that I could figure out how to do the film with a minimal number of set-ups that could be cut together in such a way as to give the effect that you want.

"Then there's working with the actors, which is something the writer never has to do. That goes to a question of not being married to your material and being willing to accomodate the cast and/or polish. It's like playwrights who have rehearsals and tryouts. This is because the way something reads on the page is not the way it sounds on its feet. The dramatic values can change, or the actor brings something new to it. You discover something you didn't think was there. It's really complicated, yet it's instinctive. Anyway, that's a very long answer to that question.

"The genesis of FRIGHT NIGHT," Holland explains, "was really my desire to do 'the boy who cried wolf,' but updated for the 1980s. I also have a tremendous affection for vampire strories, and those two interests seemed like a natural combination for a screenplay.

"One of the reasons that the genre faded was that vampire films were done as period pieces during their heyday, and nobody could figure out how to contemporize them. the parody is usually the last gasp of the genre, and I guess damn near ten years ago it was LOVE AT FIRST BITE, which I thought was very funny. Then I got outraged when I saw THE HUNGER. It was godawful, because it was a picture ashamed of the genre. It didn't mention the word vampire once. I wanted to bring it back.

"I tried to give the film some validity for a modern audience by rooting it in reality. For the first third, try selling the fact that this is happening in a real town, to a real family, to a real boy. Just to build up a willing suspension of disbelief for the audience. Once you've done that, you can get as fanciful as you want. I'm not sure what FRIGHT NIGHT is. It's a horror-fantasy-comedy, yet it doesn't poke fun at the genre, per se. It's very faithful to the traditions of the genre. I was determined to respect all the conventions of a traditional vampire story--coffin-beds, empty mirrors and the like--but to place them in a contemporary context."

To create a sense of believability, Holland assembled a cast he felt could realistically translate his script to the screen. The results were even better than he hoped.

"I was thrilled with every one of my actors," he says, "and there aren't a lot of directors who could say that. Every one of them played an important part in helping root the film in reality, and making it work so successfully."

He compares FRIGHT NIGHT's mixture of horror and humor to John Landis' AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON.

"It's a good time," he says, "like a roller coaster with laughs and screams and more laughs. It's like 'Creatures Features'--something we all grew up with, and I think it's a very positive film, as strange as that sounds. I was also attracted to vampires in particular because they're a metaphor for seduction. Look at all the fun you have if you're a vampire. You get to sleep all day, sleep with any girl you want and never die. That's not a bad life. There are a lot of psychological undertones that give it texture. I think if you took the vampire element out of FRIGHT NIGHT, you would have a very valid story about a teenaged kid who's losing his girl to a very cool older guy. If it was played on that level, it would be as psychologically valid as it is now.

"I sincerely wanted to differentiate between FRIGHT NIGHT and FRIDAY THE 13TH, and the other slasher films. With the horror, there's a lot of sweetness and humor. I wanted to give people a feeling of fun like I had when I was 14 or 15 and would sit home on Friday nights watching 'Creature Features,' making out with my girlfriend and trying to feel her up at the same time. To get back to that sense of innocence. There were guys coming out of coffins on some of the most terrible sets you've ever seen..." he trails off with a laugh.

"I tried to mix in all those qualities as opposed to blood and gore. It is not blood and gore. That's not to say that the film doesn't deliver. There are some points there where you'll be jumping out of your seat, but I'm not doing it by throwing chicken blood all over the place. We worked together to make this a classy first rate film."

Judging by the scripts he's written, the impression is that Holland holds a certain fascination for tortured individuals.

"Actually, I'm more interested in psychological suspense," he differs, "although Norman appeals to me. I love Norman, but who doesn't love Norman Bates? But, no, I wouldn't say so. What's interesting, what I like to do, is create a disturbing sympathy for the villain, and there should be something not very likeable about your hero. It's a more complex experience for the audience. A great example of that, I think, is Alfred Hitchcock's VERTIGO. Kim Novack is the villain, but you start to feel sympathy for her. Jimmy Stewart is the victim and hero, but he's so obsessed that you start to dislike him. That is certainly the ambivilence you feel. It's what makes PSYCHO II, a lot of Hitchcock movies and, hopefully, some of mine so successful creatively, and gives the characters some emotional resonance."

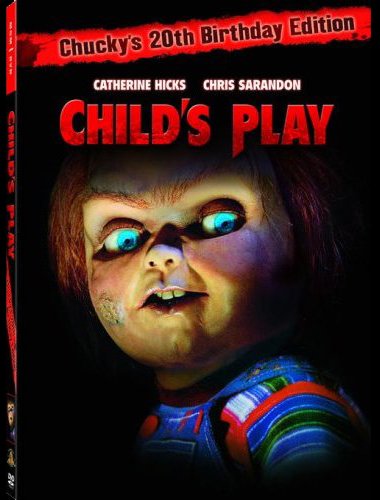

Dismissing his next film, FATAL BEAUTY, as an "unpleasant" experience, Holland turned back to the supernatural with CHILD'S PLAY, a film that has afforded him the opportunity to do what he does best: control the audience.

"I remembered a TV movie by Dan Curtis called TRILOGY OF TERROR, where he did three shorts with Karen Black, and I thought the one he did with the Zumi-doll was terrific. I also thought that if there was a way of doing that as a feature, with the new advances in special effects, it could be something very special. I also think there's something primal about your playthings coming alive. So I was interested in doing a story about a doll, and was trying to come up with an idea," Holland relates between set-ups of the film. "United Artists and [executive producer] David Kirschner came to me with a screenplay by Dan Mancini, and it was like an extended episode of THE TWILIGHT ZONE. I liked the concept, and I guess I was the first writer/director on it, but I couldn't solve it.

"In Don's version, the doll was actually the boy's alter-ego. They were blood buddies, having exchanged blood with each other, and whenever the boy went to sleep, the doll came to life and killed whoever the boy was angry at, whether it be his dentist, his teacher or his babysitter. What happened is that you disliked the little boy, and it was uncomfortable to me to make a six or seven year old boy culpable. If he was 12-14 it wouldn't have mattered as much, but not at that age."

In his revised script (cowritten with Mancini and John LaFia), a mother buys her son a "Good Guy" doll named Chucky, which plays host to the soul of a killer. "This story is very keyed in to today," explains Holland, "given all those $130 dolls that are sold around Christmas. It's about the pressures that TV ads exert on little kids. But the main thing I wanted to do was make the boy the victim and the audience like him. So now the doll is possessed by a serial murderer, and is seeking vengeance, with the boy being blamed for it."

One thing Holland wants to make clear about this Cabbagepatch nightmare is that it is not a horror film. "I don't do horror," he says. "I do psychological suspense. I believe you'll find that at least the first 60 minutes of this movie are very suspenseful, rather than horrifying."

He describes a series of sequences from the film, almost acting them out as he does so. "I'm going in cutting order," he says. "The babysitter is in the kitchen and hears a sound that turns out to be a mouse. She moves away, and then a toy hammer wipes frame and hits her in the head. Then I cut down to the floor and go to pumping feet, which is the Hitchcock shot from PSYCHO of Martin Balsam. Then I dolly and zoom with her, pushing closer and closer. I insert a shot of her hand grasping the table for balance, but she only rakes everything from the table. Then there's a tight shot of the actress smashing in the window and we cut outside to see the stunt girl going out."

Actor Chris Sarandon, who was the vampire in FRIGHT NIGHT and a cop in CHILD'S PLAY, praises Holland's growth as a director. "He's more sure of his craft now. He's very smart; he knows what he wants and he has a big ego, which is good for a director unless it gets in the way of his work. But Tom doesn't allow that to happen."

"I really think my work in this picture is a step forward," Holland, who has recently directed an episode of HBO's TALES FROM THE CRYPT and the CBS TV-movie THE STRANGER WITHIN, agrees. "I have a greater sense of control. Each film is another step I've taken, and I'm finding that I'm able to do more complicated things, or maybe it's because things are becoming simpler as I go on."

Working with Chucky, the animatronic doll, wasn't quite so simple. "Chucky represents the most sophisticated puppetry ever, although there have been some problems," says Holland. "The main thing is that the audience has to maintain its suspension of disbelief. They had to believe that a doll three or four feet tall could really be a threat, because common sense tells you that all you have to do is lift your foot and crash down. So trying to make that doll work was a big technical problem. It took nine puppeteers to operate the doll, so you had to give the technicians a lot of rehearsal time to give them a chance to coordinate its movements, the eyes, the smile, the lips and all of that. I also couldn't stay on Chucky too long, or else the audience would really start to notice that it was a puppet rather than a 'living' thing. By cutting quickly from the doll, it helped to maintain the illusion, but the problems were many.

"God said don't make effigies, so I guess this is His way of paying us back," Holland laughs.

Not only has there been a CHILD'S PLAY 2 and 3, but a FRIGHT NIGHT II as well, and Holland has avoided them all.

"What they usually do is make sequels cheaper, and they're derivative of the original," he says. "If someone says, 'Let's do a second one bigger and better,' then fine, but nobody ever does that. They all come and say, 'Let's make one that's smaller and make money off of the success of the first one,' and that's what happens. Does the audience love Chucky enough to see him killing more people? I don't think so, but the studio seems to think that they've got another Freddy Krueger here, and that's what's driving the idea of sequels. They think a property is pre-sold, so they don't even try.

"It's very hard," Holland adds. "Hollywood sort of looks upon horror movies as their money-making step children. Yes, they're wonderful to make money with, but, God, they don't want their name on one of them. The studio system is not behind horror movies the way they are behind star movies or general audience popularity movies. The executives don't really have a taste for horror films, so it's difficult for them to judge them.

"Personally," he muses, "I think the reason I've probably enjoyed success with these films is that I bring a comedic and suspenseful sensibility to the horror genre. God knows that the genre scripts sent to me are either heavy effects or serial murders. There's not a lot that's original right now, and I need to feel that there's something special there to get me interested."

|

0

|

|

|

0

|

|

|

|

EdGross

5/31/2010

DISCLAIMER: This posting was submitted by a user of the site not from Earth's Mightiest editorial staff. All users have acknowledged and agreed that the submission of their content is in compliance with our Terms of Use. For removal of copyrighted material, please contact us HERE.